So as a "movie" person it seemed

de rigueur to see the new Tarantino joint,

Once Upon A Time...In Hollywood.

Funny title. It's a reference to Leone, of course. But also that fey ellipsis suggests a fairy tale or a Disney princess movie from the '90s.

Spoiler alert! (Every article about

Once...Hollywood requires a spoiler alert.) It's a Disney princess movie after all.

Not in the text, to be clear. There's a kingdom, and an oppressive hierarchy that prevents our hero from finding true love and happiness. The historical longevity of this kingdom is suspect but subliminal (the functional industrial mechanics are depicted in quotidian details. Fancy camera moves, an actor's dilemma.). The film is chaste; no one's looking to get laid. (The wife, apparently accidentally acquired and barely able to speak English, serves as a distraction and is put back to sleep when her plot use is over. There aren't even any topless women in the Playboy mansion sequence.) Nothing really hedonistic or Fatty Arbuckle about this version of Hollywood.

Our dreamy lead just wants to be with the person he loves the most. You know those movies where the hero asks the girl if she wants to go get a soda and when she says yes it's like the most important triumph of his life? Here he wants his buddy to watch his TV show with him, and when he's already bought the beer and has a plan to order pizza, there's an emotional sense of unspoken camaraderie that's strangely touching at that moment.

And it even has a happily ever after. Our lovers are separated physically, but only until tomorrow, and they're as close as a hand on a piece of glass. This isn't

First Man hand on a piece of glass. This is

Pickpocket hand on a piece of glass. "Visit me in the hospital," he says. You know he will.

But to be clear, it's also a Leone western. Gunslingers fighting in the landscape of long ago, when things were simpler, fighting forces larger than one man. Dispensing personal hand-to-hand justice when the system, whether it be corrupt oil barons or cynical Hollywood hangers-on, oppress those around them.

Plus, there's sure an inordinate amount of TV western footage in this. Does that make it a western or just a film with westerns in it? Hold that thought.

And like all Leone's westerns (even

Once Upon A Time... in America), it's about the death of the frontier. The coming of the railroad. In its way, civilization (whether in the form of Claudia Cardinale or the Teamsters) means the good times are coming to an end.

And what does Tarantino do with this meta/ post-modern conceit? Hollywood fairy tale as western? He makes it a love letter, but he needs an ending. Instead of the railroad coming to town or Ms. Cardinale marking fenceposts on the homestead, he turns to the one event in numerous biographies that mark the death of the Hollywood scene. That day in 1969 when Tate & co. were visited on Cielo Drive by Manson's girls. And Tex.

Tex. Yee-haw. Yes, it's a western all right.

We've heard it many times and not just from (but maybe originating from?) Joan Didion. The hippy vibe turned dark that month. You couldn't keep your door unlocked or pick up hitchhikers anymore. Both featured prominently in this film (

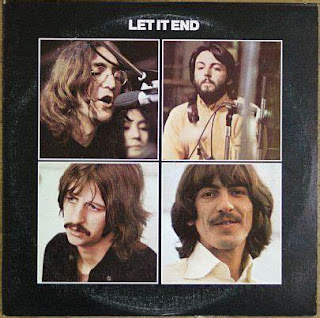

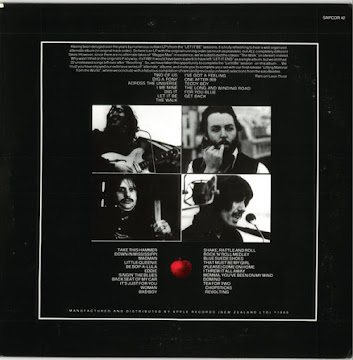

Spoiler alert!). The rich turned inward. And three months later it's Altamont. What was next, the Beatles breaking up? Like I said. He ends up making it a fairy tale. If only real life could be like this.

Tarantino makes the ultimate hang-out movie, spending 2+ hours recreating the end of the '60s, channeling

Route 66 and Jacques Demy's

Model Shop, and withholds until he can't anymore, a final scene of the

Wild Bunch ultra-violence, that's cathartic, problematic, beautiful. Stops time.

But because of that, it's hopelessly inconclusive. That car did drive away with the woman who still has a knife, after all. We know what happens next... or do we?

And Sharon Tate lives to make more movies, though probably no more with Roman Polanski. Even though in this film, she's already dead. A dream of lost potential, frozen in the moment where fame is nothing more than a 50-year-old doorman in a theatre who lets her in for free. The same theatre where Julian Kaye confronts Stratton's henchman in

American Gigolo.

There are two Hollywoods. The one we wish were true and the boring reality behind the scenes. There are two Rick Daltons, one who cries when he blows a line and one who killed his wife. (Or at least, doubled by one who did.) There are two Sharon Tates, the one up on the screen who walks in a kind of blessed bliss, and the one who never rose above true-crime footnote. There's the end of the '60s, and the false historical pause that allows them to continue on in our dreams, at least past the credits, at least for a little while.

And boy howdy, Tarantino is going to give his version the deepest rabbit-hole Thomas Pynchon treatment he can. Reference after reference, neon signs and real-time

TV Guide covers, fake movies and deep-cut album tracks. Kurt Russell as a stuntman and actors who didn't wear helmets on their motorcycles in real life. What is fake and what does the stuff in the background really mean?

Every movie title you see is one of those old stuffy Otto Preminger movies (or might as well be). Not a reference to

Midnight Cowboy (1969)

, Medium Cool (1969), or

Easy Rider (1969) (besides a dismissive aside) in sight. Even the set design is in denial about the brick wall that's about to be hit.

Every corner is filled with something. A piece of an Italian locandina, Steve McQueen who famously claimed he was invited to the bungalow that night but ended up going with another girl (because he wasn't Sharon's type anyway), none of which is explained in this movie but it's all right there for those who are not blind.

It's almost too much. Your eyes and your ears can't see it all, can't see enough, are taking in too many things. Subtext, inferences, nods and indulgent pauses. Artifice and the makings of it. We get fan service, Pitt takes off his shirt, we get fetishistic close-ups of needles literally dropping on records and almost too many shots of feet, bare and shod. Beautiful close-ups of headlights.

And yet not a single shot of someone tuning or turning on a car radio. It seems whenever you start a car the music simply starts. You don't get to see a stereo dial in close-up until you've smoked a little LSD. Which is perfect.

My ultimate opinion of the film is mixed at the moment. Which is how I judge most recent Tarantino films. I see them two times or even three, and the good parts get better and the bad parts become worse. Can't ever write them off, though. They're still the best movies to talk about in the lobby when you're a bored usher (as in my earlier formative years).

This thing's a dream, veers close to being a nightmare just to pull the celluloid curtain away (or over) at the last moment.

...Hollywood is incredibly well-made and Tarantino's confidence has built to the point where he can spend what seems like 20 minutes recreating a melodramatic late '60s horse-opera scene shot on a sound stage (with over 10 minutes of lead-up) that's pure minor back-story, a scene any other director in any other era, pre- or post "golden age," would have cut down to 2 minutes. Or completely.

It's indulgent, delicious in how it recreates the fantasy of the industrial complex, too long and yet never boring. Even as it disingenuously foregrounds what happens in front of the camera as more important than what happens behind, or in preproduction or in post.

Tarantino knows damn well how important good, compelling performances are to the success of films -- we refer you to Travolta in

Pulp Fiction which I maintain is the primary reason that film didn't tank under its own weight. But who wants to see where the real work happens, in the research department, in razor cutting, designing crane shots, when we all know we're happier watching Brad Pitt drive around in a DeVille listening to the Mamas and the Papas.

So what to make of this technicolor object, told with careful and indulgent care, a shiny object floating in the sea of sequels hiding an iceberg of work and references, and soaking with cultural artifacts made important purely by the attention being bestowed on them even as they remain out of the direct spotlight?

DeCaprio's Roman adventure ("Roman") is either a brilliant nod to the industrial function of international funding practices in the '60s or just a visual rhyme/pun. Rick Dalton uneasily moves towards domestication at the end. Is his new wife his Claudia Cardinale, his civilizing influence, or an excuse to get a girl in her underwear on screen a moment for the big finish?

Tarantino doesn't seem to need to answer this. Probably more interesting that he doesn't. She's unimportant except as a punchline, an indicator that shirtless Brad Pitt will indeed be in the sequel. Because we know how those things go; you don't break up the team. You also leave a bad guy to come back because next time it'll be more personal.

I know that won't really happen.

Spoiler alert.

On the first viewing my enjoyment of this film is in direct relation to how much I know the back story. I drove those streets in LA and Burbank. I've seen those movies and played with those toys. The movie seems to be going for something more, but I'm not sure it gets there or even exactly where that is. I imagine a younger generation who didn't grow up watching episodic westerns on TV or who don't know what Spahn ranch is or what Charlie's girls did and would do, who might find this film incomprehensible.

That's part of its charm. It's a focused valentine to one person, speaking a secret language. Quentin, it's taken me so long to come to you.

|

| * screengrab from the blog http://movie-tourist.blogspot.com/2013/05/american-gigolo-1980.html |